An Intuitive Guide to Neural Networks

Neural Nets from Scratch in NumPy | ML from the Fundamentals (part 4)

In this post you will build a classifier model to classify images of handwritten digits. This may sound like a rather complicated problem to solve (what is “the number 5”?). However, by using the power of machine learning we do not have to define each number; it will learn by itself. Along the way I will introduce you to the most powerful classifier yet: neural networks. Entering deep learning for the first time.

I am aware of the fact that due to their insane success, many tutorials have been written about neural networks. Many try to impress you by giving a vague proof of backpropagation. Others will confuse you with explanations of biological neurons. This post is not yet another copy of that, nor will I be ignoring the mathematical foundations (which is contrary to the goal of this series). In this post I hope to give you an understanding of what a neural network actually is, and how they learn.

Here is the corresponding notebook where you can find a complete and dynamic implementation of backprop (see later) for any number of layers.

The dataset

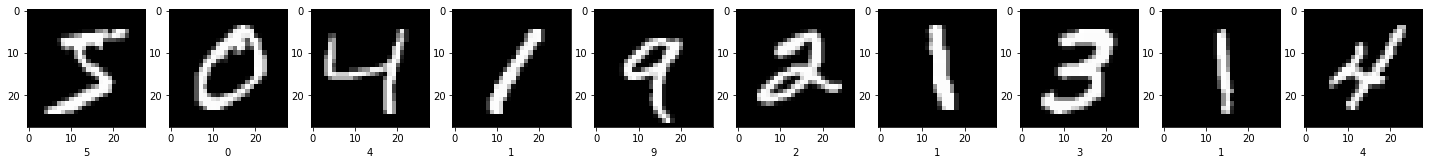

As I just mentioned, in this post we will classify handwritten digits. To do so, the MNIST dataset [1]. It consists of 60000 28 by 28 grayscale images like the following:

In computer vision, a subfield-ish of machine learning, each pixel represents a feature. The images in MNIST are grayscale so we can use the raw value of the pixels. But other datasets might be in RGB format and if that’s the case each channel of a pixel will be a feature.

It turns out that the classifiers we have seen thus far are not capable of classifying data with this many features ($28 \times 28 = 784$). For instance, the 4’s in the images above are quite different, most certainly when represented as a matrix.

This does not mean the problem cannot be solved. In fact, it is solved. To understand how, let’s learn about neural networks.

Classification models as networks

Think about a classification as follows

where $x$ is an input vector, being mapped to a prediction vector $\hat{y}$.

If you were to visualize the individual elements of both vectors, you would get something like this:

Let’s look at the definition of the hypothesis function $h$ again: (see softmax regression):

\[h_\theta(x) = \sigma(X \cdot \theta) = \begin{bmatrix}p(y = 0 | x; \theta) \\ p(y = 1 | x; \theta) \\ p(y = 2 | x; \theta)\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\exp(\theta_0^Tx)}{\sum_{j=1}^k \exp(\theta_j^Tx)} \\ \frac{\exp(\theta_1^Tx)}{\sum_{j=1}^k \exp(\theta_j^Tx)} \\ \frac{\exp(\theta_2^Tx)}{\sum_{j=1}^k \exp(\theta_j^Tx)} \end{bmatrix}\]The most important thing to understand is that every feature $x_j$ is multiplied by a row $j$ in $\theta$ ($\theta_j$); each feature $x_j$ impacts the probability of the entire input $x$ belonging to a class. If we visualized the “impacts” in the schema, we would get this:

One thing this graph does not account for is the bias factor. Let’s add that next:

The network seems, on a high level, very representative of the underlying math. Please make sure you fully understand it before moving on.

Nodes in the graph

Let’s now look at an individual node in this network.

The node for $\hat{y}_1$ multiplies the inputs $x_j$ by their respective parameters $\theta_j$ and, because we are dealing with vector multiplication, adds up the results. In most cases, an activation function is then applied.

\[\hat{y}_1 = g\left(\displaystyle\sum_{j=0}^n \theta_j \cdot x_j\right)\]This is the exact model we discussed in the logistic regression post.

In the context of a classifier network, people call nodes such as $\hat{y}$ “neurons.” The complete network is, therefore, considered a “neural network.” For the sake of consistency I will also use those terms, but I will simply define “neuron” as “node.” Keep in mind that the biological definition of neuron is something else entirely.

Extending the network

Simple networks like these, it’s just a logistic classifier represented as a network, fail at large classification tasks because they have too few parameters. The entire model is too simple and it will never be able to learn from more interesting datasets such as MNIST. However, logistic regression can still be used in this problem. In fact, the main intuition I will present in this post is that a neural network is just a chain of logistic classifiers.

The graph I presented before can be modified to include another layer, or multiple other layers, the so-called “hidden layers.” These layers are placed between the original input and the original output layer. The reason they are called “hidden” is because we do not directly use their values; they simply exist to forward the weights through the network. Note that these layers also have a bias factor.

Because the hidden layer (blue) is not directly related to the number of features (the input layer, in red) or the number of classes (output layer, in green) they can have an arbitrary number of neurons, and a neural network can have an arbitrary number of layers (denoted $L$).

Weights

This schema looks promising, but how does it really work?

Let’s start by looking at how we represent the weights. In the first two posts (polynomial regression and logistic regression) the weights were stored in a vector $\theta \in \mathbb{R}^n$. With softmax regression we started using a matrix $\theta \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times K}$ because we wanted an output vector instead of a scalar.

Neural networks use a list to store weights, often denoted as $\Theta$ (capital $\theta$), each item $\Theta^{(l)}$ being a weight matrix. Unlike the schematic, the shapes of the hidden layers often change throughout the network, so storing them in a matrix would be inconvenient. Each weight matrix has a corresponding input and output layer. A particular weight matrix, in layer $l$, is $\Theta^{(l)} \in \mathbb{R}^{(\text{number of input nodes} + 1)\atop \times \text{number of output nodes}}$.

A Python function initializing the weights for a neural network:

# inspired by:

# https://github.com/google/jax/blob/master/examples/mnist_classifier_fromscratch.py

def init_random_params(layer_sizes, rng=npr.RandomState(0)):

return [rng.randn(nodes_in + 1, nodes_out) * np.sqrt(2 / (nodes_in + nodes_out))

for nodes_in, nodes_out, in zip(layer_sizes[:-1], layer_sizes[1:])]

This function takes a parameter layer_sizes, which is a list of the number of nodes in each layer. For this problem I build a neural network with 2 hidden layers, each with 500 neurons. Note that the number of nodes in the input and output layer are determined by the dataset.

weights = init_random_params([784, 500, 500, 10])

init_random_params automatically accounts for a bias factor, so we get the following shapes:

>>> [x.shape for x in weights]

[(785, 500), (501, 500), (501, 10)]

Computing predictions: feedforward

To compute the predictions, given the input features, we use a (very simple) algorithm “feedforward.” We loop over each layer, add a bias factor, compute the output by multiplying by the corresponding weight matrix, and finally apply the activation function.

It’s easier in Python:

def forward(weights, inputs):

x = inputs

# loop over layers

for w in weights:

x = add_bias(x)

x = x @ w

x = g(x)

return x

Given the list of weights $\Theta$, we know that given the input $x = a^{(1)}$, the activations in layer 2 should be $a^{(2)} = g(x \cdot \Theta^{(2)})$. The activations in layer 3 should be $g(a^{(2)} \cdot \Theta^{(3)})$. Generally, the activation in layer $l$ is $g(a^{(l-1)} \cdot \Theta^{(l)})$. Note that the above code example uses x as the only variable name for convenience, but that does not necessarily mean $x$ as in input.

In short, $h_\theta(x)$ can take on other forms than a matrix multiplication.

Training: backpropagation

Next, let’s discuss how to train a neural network. People often think this is a very complicated process. If that’s you, forget everything you’ve learnt so far because it’s actually quite intuitive.

Once you realize that the values for any $\Theta$ yield deterministic activations in the entire neural network given some input, it is understandable that not every activation in a hidden layer is desired, even though they are not directly interpreted (in fact, interpreting the values of hidden layers is an active problem). This implies that in order to have good predictions, we also need good activations in hidden layers.

We would like to compute how we need to change each value of $\Theta$ so that we get the correct activations in the output layer. By doing that, we also change the values in the hidden layers. This means that the hidden layers also carry an error term (denoted $\delta^{(l)}$), while that’s not directly obvious if you only think about the final output layer. The same thing in reverse: by inspecting the error in each hidden layer, we can compute the change (gradient) for the weight matrices.

Computing errors

The only layer for which we immediately know the error term is the output layer. Because it serves as a prediction layer we can compare its output to the labels. The error for layer $L$ is given as

\[\delta^{(L)} = \hat{y} - y\]For all previous layers we can compute the error term with the following formula:

\[\delta^{(l)} = ((\Theta^{(l)})^T \delta^{(l+1)})\ .* g'(a^{(l)})\]Because $\delta^{(l)}$ is depended on $\delta^{(l+1)}$ the error terms must computed in reverse other. It is also dependent on $a^{(l)}$, the activations of layer $l$, so in order to compute it we first need to know the exact activation in this layer. That’s the reason a full forward propagation is usually computed before starting backpropagation, saving activations along the way.

x = inputs

activations = [inputs]

for w in weights:

x = add_bias(x)

x = x @ w

activations.append(x)

x = g(x)

predictions = x

Now to compute the error term, we start by computing the error in the final layer. The error is transposed to match the format of the other errors we will compute.

final_error = (predictions - y).T

errors = [final_error]

We will compute the other errors in a loop. A few things to note:

-

We index our activations by

[1:-1]so we skip the first layer (the input has no error term) and the output layer (we already have computed that). -

We skip the first node in each layer; it is defined as 1.

-

Finally,

weights[-(i+1)]is the weight matrix indexed from the back (-1becauseistarts at 0).

These things are important things to keep in mind when doing backprop, but in this context it’s easy to understand.

for i, act in enumerate(activations[1:-1]):

# ignore the first weight because we don't adjust the bias

error = weights[-(i+1)][1:, :] @ errors[i] * g_(act).T

errors.append(error)

This snippet uses the derivative of sigmoid g_. It is defined as:

def g_(z):

""" derivative sigmoid """

return g(z) * (1 - g(z))

or

\[\frac{d}{dz} g(z) = g(z) \cdot (1 - g(z))\]Finally, we flip the errors so they are arranged like the layers:

errors = reverse(errors)

For the sake of completeness:

def reverse(l):

return l[::-1]

Computing gradients

Recall that a gradient is a multidimensional step for a weight matrix to decrease the error.

We now know the error for each layer. If we go back to logistic regression, the building block of neural networks, you can think of these as the loss of each layer. This means that we can use the same equation we developed in a previous post to compute the gradient for each weight matrix corresponding to each error term. Except the loss is now $\delta^{(l + 1)}$ and the input $a^{(l)}$.

\[\Delta^{(l)} = \frac{1}{m} \cdot \delta^{(l + 1)} a^{(l)}\]grads = []

for i in range(len(errors)):

grad = (errors[i] @ add_bias(activations[i])) * (1 / len(y))

grads.append(grad)

Congratulations! You now know backpropagation. Fun note: because we are learning multiple layers, we are doing deep learning. Just so you know.

Backpropagation for individual neurons

The way backpropagation is usually taught is by presenting it as a method for finding the derivative for the cost function. A great intuition on backpropagation from that perspective is written by Andrej Karpathy in his Stanford course. I’ll let him explain it himself.

The training loop

Because the entire dataset consists of $60000 \cdot 28 \cdot 28 \approx 4.7 \cdot10^7$ elements, it’s too big for most computers to fit in the RAM at once. That’s the reason we use “batching”, loading only a few (100 in this case) at a time.

lr = 0.001

for epoch in range(2):

print('Starting epoch', epoch + 1)

for i in range(len(x_train)):

inputs = x_train[i][np.newaxis, :]

if x_train[i].max() > 1: print('huhh', i, x_train[i].max())

labels = T([y_train[i]], K=10)

grads = backward(inputs, labels, weights)

for j in range(len(weights)):

weights[j] -= lr * grads[j].T

if i % 5000 == 0: print(stats(weights))

This should get you an accuracy of $90\%$.*

For the complete code, refer to the notebook.

Deep learning frameworks

You might be wondering if you need to implement everything we did today when you are building a neural network. Fortunately, that’s not the case. Many deep learning libraries exist, PyTorch and TensorFlow + Keras being the most popular.

While this series focusses on the fundamentals, I would like to show you an example in Keras because it’s the easiest, in my opinion. (you should be able to find other tutorials on MNIST in all other frameworks easily if you’re into that)

You can define a model as just a list of tf.keras.layers objects, and Keras will automatically initialize the weights.

model = tf.keras.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Dense(500,

activation='sigmoid',

input_shape=(28 * 28,)),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(500, activation='sigmoid'),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(10, activation='sigmoid')

])

What’s next?

*This model does not have the same accuracy some other models do because I skipped some things to keep the post concise. In a future post I will present those techniques.

Apart from the ability to stack logistic classifiers, another thing that makes neural networks powerful is that we can combine different kind of layers. Today we have looked at “dense” layers, layers consisting of a matrix multiplication and activation function. Convolutional and dropout layers, for example, are other type of interesting layers I will cover in a future post.

In the next post I will cover optimization algorithms so we can train larger neural networks much faster.

Learn more

You should check out the TensorFlow Playground, a website where you can play around with neural networks in a very visual way to get an even better intuition for how feedforward works.

I added [2] as a reference to learn more about backpropagation as a technique to differentiate the loss function for neural networks.

References

[1] LeCun, Y., Cortes, C., & Burges, C. (2010). MNIST handwritten digit databaseATT Labs [Online]. Available: http://yann. lecun. com/exdb/mnist, 2.

[2] Atilim Gunes Baydin and Barak A. Pearlmutter and Alexey Andreyevich Radul (2015). Automatic differentiation in machine learning: a surveyCoRR, http://arxiv.org/abs/1502.05767.

Thanks for reading

I hope this post was useful to you. If you have any questions or comments, feel free to reach out on Twitter or email me directly at rick_wierenga [at] icloud [dot] com.